Road Safety Manual

A manual for practitioners and decision makers

on implementing safe system infrastructure!

Road Safety Manual

A manual for practitioners and decision makers

on implementing safe system infrastructure!

This section presents a brief summary of road safety management system frameworks and related tools for jurisdictions and organisations. The user of this manual is encouraged to consult original sources and the links to detailed information about road safety management frameworks, tools and their use, which are provided throughout the section.

Countries with the safest road networks demonstrate many common characteristics in their management of road safety. They have targeted better safety outcomes, adopted a systematic approach to intervention, and put in place a range of institutional arrangements which have been built up over many years (OECD, 2008; GRSF, 2009, 2013).

For more information:

These tools are designed to assist decision-makers and practitioners anywhere in the world in developing sustainable management systems. They outline pragmatic steps to build initial capacity to achieve road safety results. These tools are designed to be mutually reinforcing. They provide guidance on accountable, results-focused institutional management; promote the adoption of the Safe System goal and approach with interim targets and encourage implementation of demonstrably effective interventions to address known risk factors associated with death and serious injury in road crashes.

The main focus of this section is the country or jurisdictional road safety management system. A brief outline of the international standard for organisations is given in Institutional Management Functions in Management System Framework and Tools.

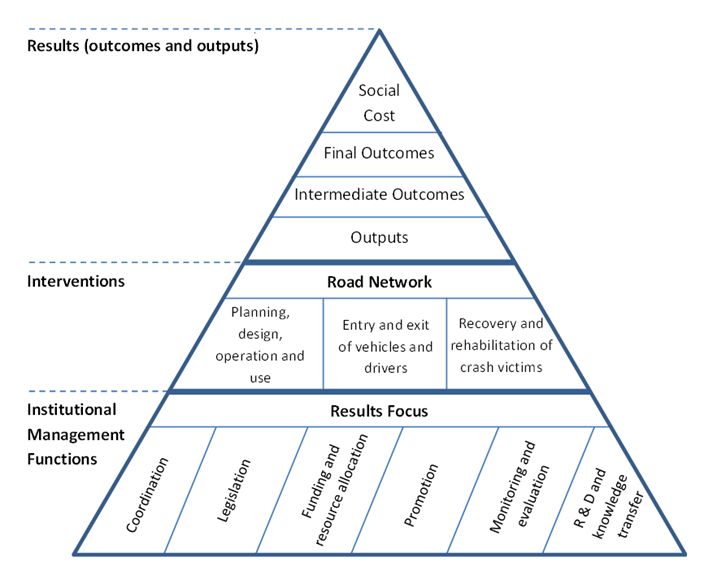

A road safety management assessment framework has been developed based on effective practice which identifies those elements of management that are crucial to improving country/jurisdictional road safety performance (GRSF, 2009; 2013). Safety is produced just like other goods and services and the production process in the framework illustrated in Figure 3.1, is viewed as a management system with three levels: institutional management functions produce interventions, which in turn produce desired results.

The following sections provide a brief description of the three management system elements shown in Figure 3.1.

The foundation of an effective country road safety management system is institutional management, as indicated in the bottom level of the pyramid shown above. Key elements of effective institutional management have been identified and defined through global study of management systems and leadership arrangements in countries and jurisdictions that have achieved substantial reductions in deaths and serious injuries (as well as those in countries without such arrangements and which have been less effective) (OECD, 2008; GRSF, 2009; 2013, GRSF 2006–09, ITF 2016). These are outlined in Box 3.1.

Source: GRSF, (2009).

The overarching function and the rationale for the management system is to reduce crashes leading to fatal and serious injuries (results focus). This represents the expression of a country or jurisdiction’s desire to achieve better road safety results through performance review; analysis of the scope for crash reduction efforts, setting long-term goals and interim targets for road safety strategies, programmes and projects and providing the means and accountabilities needed to achieve them. The delivery of this function is discussed fully in Road Safety Targets, Investment Strategies Plans and Projects. Supporting this key function are defined arrangements and capacity for coordination, legislation, funding and resource allocation; promotion; monitoring, analysis and evaluation, research and innovation, knowledge development and transfer. In the absence of a clear and accountable focus on fatal and serious crash reduction, all other institutional management functions and interventions lack cohesion and direction, and the efficiency and effectiveness of safety initiatives can be undermined (GRSF, 2009; 2013). For these reasons and as advised in Road Safety Targets, Investment Strategies Plans and Projects, LMICs should exercise caution in establishing complex targeted strategies and plans until data and appropriate management capacity are available. However, measurement of safety performance and targeting specific results is recommended in funded, ‘learning by doing’ demonstration corridor/area projects.

Institutional management functions are delivered primarily by the government agencies with core road safety responsibilities – e.g. transport, land-use planning, roads, justice, police, health, occupational health and safety and education. They are also delivered in government partnerships with civil society and business, in alignment with country and organisational goals and targets. The professional and research community provide key support for demonstrably effective next steps. As highlighted previously, governmental leadership and the setting up of a governmental lead agency are prerequisites for successful activity (Peden et al., 2004; OECD, 2008, GRSF, 2009, 2013).

Institutional management functions and examples of their delivery are referred to throughout this manual. A range of in-depth case studies which illustrate successful country delivery can be found in Annex 2 and Annex 4 of the road safety management guidelines produced and used by the World Bank (GRSF 2009).Road Safety Targets, Investment Strategies Plans and Projects as well as Annex 3 and Annex 4 of global road safety management guidance (GRSF 2009, 2013) provide guidance on establishing or strengthening lead agency arrangements.

The second element of the road safety management system framework outlined in Figure 3.1 is system-wide intervention. Effective intervention focuses on the implementation of evidence based approaches to reduce exposure to the risk of death and serious injury; to prevent death and serious injury; to mitigate the severity of injury when a crash occurs, and to reduce the consequences of injury. Interventions need to address the safety of all users and take future demographics into account, notably the physical vulnerability of very young and of the ageing society.

A common misperception in countries getting started in road safety is to assume that since 90% of crashes may be due to human error, then direct approaches relying heavily upon education and training play a substantial part in saving lives and preventing serious injuries. Although these measures play a supportive role, there is little evidence to confirm that education and training, alone, will achieve road safety results. Speed management, the safety engineering of vehicles and roads and improvements in the emergency medical system response are observed to play the major role (Peden et al., 2004). At the same time, the Safe System goal requires the examination of contributory factors in road safety engineering and other interventions to shift from a focus on crash prevention to a focus on death and serious injury prevention. Again, research on contributory factors to deaths and serious injuries indicates that intervention to improve speed management and the intrinsic safety of vehicles and the road environment all have a major role to play in addressing this new focus (Stigson et al., 2011).

The Global Road Safety Facility (GRSF) has developed an evidence-based guide on "what works and what does not work" when selecting and applying road safety interventions that are effective in reducing fatal and serious injuries (Turner et.al., 2021). The guide highlights that not all road safety interventions are equally effective and that what appear to be "common-sense" interventions will often not be the best, and in some cases may have very limited or even negative impacts, despite being commonly - and mistakenly recommended or accepted. The guide sets out evidence and presents case studies on interventions within a Safe System context and with a focus on LMICs, although the information presented is of relevance to all countries.

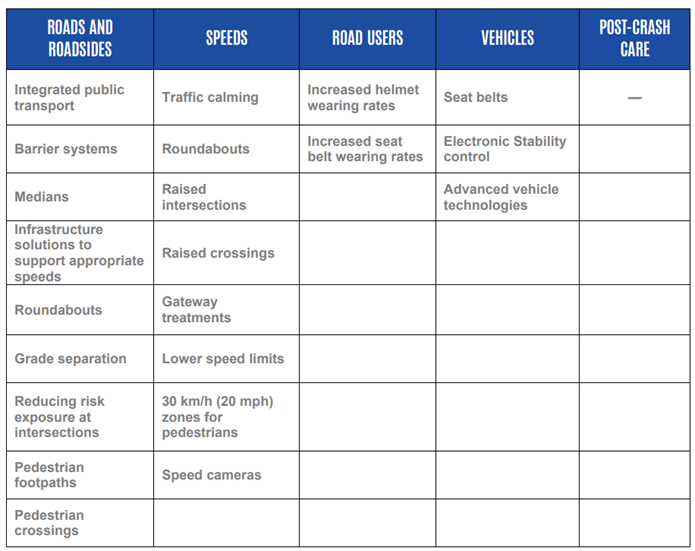

Better performing countries implement integrated packages of road safety interventions that have demonstrated significant performance gains as well as implementing innovation based on established safety principles. The findings of the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention provide a substantial consensus-based blueprint for country, regional and global action, and have subsequently been endorsed by successive United Nations General Assembly resolutions (Peden et al., 2004). Reports by the OECD, ITF and World Bank (e.g., OECD, 2008; ITF, 2016; Turner et. al., 2021) also provide international reviews on the effectiveness of interventions. Information is also available from the SUNflower study (Koornstra et al., 2002), the European Road Safety Observatory (2014) and guidance produced by the UNRSC (2006–13). Key recommended intervention strategies include:

Examples of highly effective road safety interventions within a Safe System context are highlighted in Box 3.2.

This manual is intended to provide clear and accessible information on the effective management of road safety infrastructure with a focus on the selection and application of road infrastructure interventions. To produce rapid results, road safety programmes must initially target high concentrations of crash deaths and serious injuries on secotions of the road network where the biggest gains can be made.

The planning, deisgn, operation and use of the road network is generally called road infrastructure safety management (RISM) as described in teh 2008 EU directive (and as outlined in Part 3 of this manual). The products and services used within RISM address the conditions under which vehicles and road users can safely use the road network combined with the safe recovery and rehabilitation of crash victims. In all these areas, specific standards, rules, guidelines, policies and protocols are set with compliance and oversight mechanisms in place

This manual does not set out to provide detailed guidance on road safety intervention in general but relates specifically to the planning, design, operation and use of the road network within the context of the RISM process.. See Part 3 Chapter 9 Infrastructure Safety Management and Chapter 10 Risk and Issue Identification for information on the RISM processincluding approaches to infrastrucutre safety management and assessing road network risks, respecitvely. Then, see Chapter 11, Intervention Selection and Prioritisation for guidance on intervention selection and prioritisation to address these risks. Here, cross references are also made to key work carried out by PIARC which includes its recent work and guidance on road hierarchies which provide a fundamental framework for safety management of the road network.

The final element of the road safety management system shown in Figure 3.1 concerns the measurement of results and their expression as targets in terms of final outcomes, intermediate outcomes, and outputs (Bliss, 2004). Targets define the desired safety performance endorsed by government at all levels, stakeholders and the community. The level of safety is ultimately determined by the quality of interventions that have been implemented, which in turn are determined by the quality of the country’s delivery of institutional management functions. The GSRF highlighted a few examples of success in Leveraging Global Road Safety Successes (2016)

Final outcomes can be expressed as a long-term goal for the future safety of the road traffic system (e.g. as in Safe System, Vision Zero) and interim, short- to medium-term targets towards this expressed in terms of social costs, fatalities and serious injuries usually presented in absolute terms. They can also be measured and targeted in terms of rates per capita, vehicle, and volume of travel. See IRTAD (2014) for further discussion.

Intermediate outcomes are linked to improvements in the final outcomes and typical measures include average traffic speeds, the proportion of drunk drivers in fatal and serious injury crashes, seatbelt-wearing rates, helmet-wearing rates, the physical condition or safety rating of the road network (e.g. iRAP ratings), the standard or safety rating of the vehicle fleet (e.g. Global NCAP ratings), and emergency medical system response. See ITF (2016) for further discussion on intermediate safety performance indicators.

Outputs represent physical deliverables that underpin improvements in intermediate and final outcomes. Examples are kilometres of safety engineering improvements implemented and the number of police enforcement operations required to reduce average traffic speeds, increase seatbelt use or reduce drinking and driving. They can also correspond to milestones showing a specific task has been completed (Bliss, 2004).

Countries active in road safety are increasingly setting measurable final outcome and intermediate outcome targets. In some cases, they also set related measurable output targets in line with the targeted outcomes. As mentioned previously, in many LMICs, where capacity to implement national targeted plans is non-existent or in a fledgling state, countries are advised to adopt the long term Safe System goal but to restrict the setting of quantitative targets to funded corridor and area demonstration projects. Road Safety Targets, Investment Strategies, Plans and Projects provides guidance on road data systems, which allow the setting and monitoring of targets. Case studies are presented in Roles, Responsibilities, Policy Development and Programmes of target-setting in different contexts. See Part 3 Chapter 12 for guidance on Monitoring, Analysis and Evaluation of Road Safety Interventions.

All three elements of the road safety management system – institutional management functions, interventions and results – need to be benchmarked against identified effective practice as countries develop new projects, programmes and strategies, regardless of their stage of development (OECD, 2008). Institutionnal Management Functions in Management System Framework and Tools outlines recommended steps and available tools to assess the strengths and weaknesses of country road safety management and to implement necessary capacity building initiatives.

Guidance has been published by the World Bank to assist countries which want to improve their road safety outcomes (GRSF, 2009, 2015). These acknowledge that building effective capacity requires long-term investment and will not be achieved overnight. These address the central issue of how to shift from weaker to stronger institutional management to make this happen. The guidance outlines two practical steps to strengthen country road safety management. The first step, noted below, comprises a road safety management capacity review which helps to identify strengths and weaknesses in current approaches.

The recommended first step for countries is to carry out a road safety management capacity review. Road safety management capacity review has been independently evaluated as a cost effective, good practice tool that has been used widely in LMICs. It has also been used in Sweden and Western Australia where it has contributed to strengthening in some aspects of institutional delivery to good effect (GRSF, 2012).

Capacity review objectives: The aims of the capacity review are to:

Road safety management capacity review involves engagement with senior management in key government agencies and the private sector who are able to influence country results. The review is conducted by experienced, internationally recognised, external road safety specialists with senior management experience at country and international levels.

Capacity review steps: A country capacity review is conducted through nine distinctive steps:

Twelve checklists are used to help assess and benchmark all elements of the management system and their linkages according to effective practice (see GRSF, 2009, 2015).

Long-term investment strategy: On the basis of the review, a long-term investment strategy is developed which lays a pathway from weak to strong capacity via establishment, growth and consolidation phases of the investment strategy. These phases are discussed fully in Targets and Strategic Plans.

The first stepping stone for many LMICs in establishing their road safety activity will be to prepare road safety projects rather than embark initially on the ambitious national road safety plans foreseen in the growth phase. Road safety management capacity reviews indicate that LMICs that specify national plans without the funded capacity to achieve them are unsuccessful (GRSF, 2006–13). The practical aim is to deliver key capacity building elements in funded implementation projects, such as those outlined in Section 3.4 in the establishment phase of the investment strategy.

The project involves building core institutional capacity to measure and target safety outcomes in high-volume, high-risk corridors and areas, with specific attention being paid simultaneously to lead agency and related coordination arrangements and monitoring and evaluation. This provides a basis for the scaling up of investment to accelerate this capacity strengthening, and the achievement of improved results across the road network in a national plan for the growth phase.

The second step of the country guidance is the careful preparation and implementation of Safe System road safety projects to deliver the establishment phase of the investment strategy (GRSF, 2009; 2015). As mentioned previously, carefully prepared and funded demonstration corridor projects provide an excellent means for countries starting out in road safety or countries embarking on more ambitious approaches to build initial capacity.

Current World Bank road safety investment in capacity building efforts is focusing on systematic, measurable and accountable investment programmes. These simultaneously advance the transfer of road safety knowledge, strengthen the capacity of participating governmental partners and stakeholders, and rapidly produce results in targeted high-risk corridors and areas. The aim is to provide benchmarks, dimensions and capacity for the next stage of investment (GRSF, 2013). Recommended project components are briefly outlined in the ‘Getting Started’ material at the end of this chapter, while examples are provided in Roles, Responsibilities, Policy Development and Programmes. Complementary guidance has been issued for a streamlined approach to capacity review and project development and ‘mainstreaming’ road safety in regional trade road corridors (GRSF, 2013; Breen et al., 2013).

While the two-step process outlined above has been identified to inform investment priorities in LMICs, the above tools have also been used by HICs which have moved to a Safe System approach (Breen et al., 2008; Howard et al., 2010). Roles, Responsibilities, Policy Development and Programmes provides examples of capacity building demonstration projects that can help build leadership and coordination arrangements, implement multi-sectoral action, and achieve quick results in targeted high-volume, high-risk corridors and areas.

This section has briefly introduced capacity building tools. The main principles which underpin this guidance can be summarised as: the need to address all elements of the road safety management system in reviewing management capacity to produce results; adoption of a phased approach to road safety investment and a ‘learning by doing’ approach; targeting the highest concentrations of deaths and serious injuries across the road network and adopting a Safe System approach; and building global, regional and country road safety management capacity. Practical examples of how these tools are being used worldwide are presented throughout this manual. Readers are referred to the original guidance for a detailed discussion (GRSF, 2009, 2015).

Motor vehicle crashes are a leading cause of death and long-term injury at work and in driving associated with work. For example, surveys in several EU countries indicate that between 40–60% of all work accidents resulting in death are road crashes. Studies conducted across the world indicate that the costs of work-related crashes are substantial, both for society and employers (DaCoTA, 2012b). ). To reduce death and serious injury the International Standards Organization developed ISO 39001: Road Traffic Safety Management Systems: Requirements with guidance for use standard has been produced.

The standard is designed to assist organisations in integrating road safety as a core objective into their management systems, as well as aligning with country road safety goals and strategies. The standard is aimed at both small and large organisations, as well as the public and private sector Specific examples given include organisations concerned with transporting goods and people; those generating traffic, such as schools and supermarkets; and those responsible for provision of the road network.

The ISO 39001 standard links to other ISO management systems standards and sets out specific and wide-ranging top management responsibilities and key management functions. ISO 39001 requires organisations to adopt the Safe System goal and to make decisions on objectives and targets for the interim as well as plans to achieve them. The organisation is required to follow a process that starts with a review of its current road traffic safety performance; makes an assessment of the context for the organisation’s activity; and considers specified, measurable road traffic safety performance factors known to reduce the risk of fatal and serious injury within the organisation's sphere of influence. The organisation has to select the road traffic safety performance factors to work on and then analyse what it can achieve over time. When establishing its targets, the organisation is required to consider the management capacity required to achieve them, as well as monitoring results and reviewing its road safety management system towards continual improvement (ISO, 2012).

Early adopters of ISO 39001 include freight and passenger transport organisations and companies in Sweden and Japan. If implemented within the right national policy framework, the tool has high potential to engage employers of organisations of all sizes in effective road safety activity. In the case of LMICs, early adoption of ISO 39001 by large corporations in the first instance could assist governments in meeting their serious road safety challenges.

When the main objective is to avoid accidents on the roads, all levels of society need to make a contribution. At the highest level, the way in which society decides on its transport needs, the choice of transport and mobility, the level of provided transport equipment and facilities, the level of education of road users, etc., are all influenced. All these factors, which are controlled at the national and to some extent global level, are also of great importance for the level of road safety at the local level. However, they cannot be directly influenced by individual municipalities.

At a lower level, road safety is also the result of practical planning, iin other words, where activities are located and how the tansport system is structured. For example, the road and street system can be divided into different categories according to the activities and potential disturbances. A certain level of traffic safety required by one group of road users often contrasts with the level of safety desire by another. How different modes of transport look and how conflicts between them are prioritised is very important in determining the risks to which different groups of transport users are exposed. Longer journeys expose more people ot more risks and generally lead to more accidents. Municipalities have the opportunity to infouence this through sound planning. It is also needed to create good operating conditions for public tansport which reduces crash exposure through the reduction of vehicle volumes.

Road safety can be examined in more detail by looking at the behaviour of road users and how they use and take or reduce risk behaviours on the transport system. The transport environment places demands on the behaviour of road users, and the capacity of road users places demands on the design of the surrounding environment as it interacts with road users and how road users interact with each other can help to understand the causes of individual accidents. It is the responsibility of the municipal system and to maintain the quality level. In this respect lcoal influence is strong.

The design and planning of the municipal transport system therefore directly affects future road safety, but it is important to udnerstand that municipal planning also affects the level of road safety in the municipality well into the future. This is why road safety must be integrated into all planning of the physical environment.

In the context of extended social planning, road safety is one of many factors influencing other aspects. Other aspects also influence road safety. Balanced weighting between different attributes such as urban character, accessibility, safety, road safety and environmental impact will ensure a sustainable outcome in the long term. Features can work for or against each other and can also compete for available resources. Therefore, municipalities need to make their own priorities and adjust their investments according to their needs and resources.

Road safety affects urban space and urban life appropriate speed and well-designed urban space have synergetic effects. Road Safety can act as a catalyst for creating a more beautiful urban space and a safer more vibrant city. Improved road safety can also have positive effects on noise and air quality. More moderate speeds reduce emissions and noise. Lower speeds also reduce the attractivenss of car traffic, which reduces the flow car traffic to some extent.

Success in local road safety work requires the creation of structures and the acquisitioni of information involving several municipal functions. Different measures need to be prioritised and the most cost-effective ones selected for implementation Intervention and Prioritisation. There is a need to create continuity in the work and for municipal officials, politicians and, above all, the general public to learn to understand the problems better. To this end, a road safety programme must be drawn up, documenting the objectives and the efforts to be made, and to which a commitment must be made, and to which a commitment must be made. It will be easy to monitor progress (see monitoring and evaluation) and new programmes can be drawn up at the end of the programme period. A systematic approah is the basis not only for success but also for increasing knoledge in society a. A systematic approach requires clear objectives, knowledge of the current situation and a clear understanding of how to achieve them.